In the original 2004 Mean Girls, gossip plays out through word of mouth or surprise three-way phone calls. But in the film adaptation of the Mean Girls musical, vicious teen backstabbing gets a social media makeover.

The film, which was also written by Tina Fey, moves the classic 2000s flick to the present day, trading Y2K aesthetics for Gen Z vibes. With that shift comes the need to bring modern-day tech and social media into the movie — because how can you accurately depict the 2020s high school experience without it?

For directors Samantha Jayne and Arturo Perez Jr., the challenge became incorporating social media into this new take on Mean Girls in a way that would ring true with audiences today (especially younger viewers).

“You can’t overdo it,” Perez Jr. told Mashable in a video interview.

“It’s a balance, right?” Jayne added. “If you go too hard with it in scenes where it doesn’t count, it feels superfluous.”

They found inspiration in the framing device of the musical on which the film is based, which sees Janis (Auli’i Cravalho) and Damian (Jaquel Spivey) recounting Cady’s (Angourie Rice) encounter with the Plastics as a “cautionary tale.” With that in mind, Perez Jr. said, the vision for Mean Girls became: “Let’s do this film as if Janis and Damian directed it.”

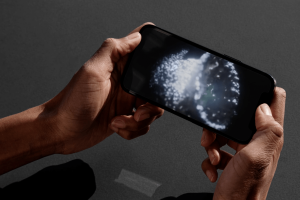

We see this right from Mean Girls‘ opening moments. Janis and Damian film themselves vertically on a phone while singing in a garage. Seconds later, the screen widens into a CinemaScope aspect ratio as we journey to Cady’s home in Africa. Throughout the film, we’ll see these aspect ratio changes time and time again, as the format jumps between widescreen and vertical phone screens. Sometimes these changes even happen mid-musical number.

How can social media shape a Mean Girls musical number?

Avantika, Angourie Rice, Reneé Rapp, and Bebe Wood in “Mean Girls.”

Credit: Jojo Whilden / Paramount

Take Karen’s (Avantika) Halloween costume banger “Sexy.” In the original stage musical, the song opens with a gag that involves Karen appearing onstage, realizing she’s messed up her song, and leaving. Seconds later, in one of the musical’s biggest applause breaks, she returns to the stage and starts all over again.

“We’re huge fans of the musical. We love how she walked out on stage, then left, and that was the joke there,” explained Jayne. “But that just wouldn’t translate [to film]. So, what would she do?” Mean Girls solves that problem by having Karen singing into her phone camera while preparing for the Halloween party, only to restart her recording when she screws up.

“We pitched that [‘Sexy’] should start as a Karen ‘Get Ready With Me‘ video,” Jayne said.

From there, Karen’s “Sexy” dance is picked up by other performers in their own videos, mimicking how TikTok dances spread. These dances come courtesy of the film’s choreographer Kyle Hanagami, whose viral dance combos are an internet staple. “He is so beloved by the internet, and he speaks internet,” Jayne said, “so he just knew how to do all of these fun transitions that all the kids do.”

Capturing the overwhelming nature of social media

Avantika, Angourie Rice, Reneé Rapp, and Bebe Wood in “Mean Girls.”

Credit: Jojo Whilden / Paramount

Beyond being a tool to add new flair to musical numbers, social media becomes a key storytelling device in Mean Girls. Think of it as an evolution of the talking heads in the original, where North Shore students tell the camera things like, “I saw Cady Heron wearing army pants and flip flops, so I brought army pants and flip flops.” The new Mean Girls sees these kinds of observations texted between friends or brought up in TikTok videos.

The role of social media becomes especially prominent in key montages, like reactions to Regina George (Reneé Rapp) falling over at the Christmas talent show or to her getting hit by a bus. Since these incidents were filmed by other students, the magnifying glass on people like Regina and Cady grows a hundredfold. Their every move is replayed and dissected for the whole world to see. (You can spot several cameos in these sequences, including rap superstar Megan Thee Stallion and influencers like the Merrell Twins and Alan Chikin Chow.) The scope and potential reach of these posts makes Cady’s experience more overwhelming than the gossip of the original, or even in the musical, which projected an onslaught of posts onto the back of the stage.

“When we dive into these barrages of social media posts, we wanted it to feel like these characters are scrolling through their phone. It’s in your face. We wanted it to feel violent, in a way,” Jayne said of the montages.

“Yeah, if you’re getting bullied, that’s what it feels like,” Perez Jr. added.

“When people are talking well of you, it feels euphoric. And when people are disparaging you and making jokes about you, it feels devastating,” Jayne said. “We wanted that to feel as real as we could make it.”

That sense of overwhelming emotion in the face of relentless social media scrutiny came in part from Jayne and Perez Jr.’s scouting of real high schools. There, they saw the impact of technology on teen life firsthand. They cited things like phones always being out and plugged in to charge in classrooms as guidance for the ubiquity of tech in Mean Girls. But what surprised them most about current teen culture was the difference between interactions in real life and online.

“[The students] kind of seemed nicer. I heard a lot of people be really nice to each other,” said Perez Jr. “So I would ask, ‘What’s going on here?’ And the kids were like, ‘Oh no, no one’s mean to your face anymore. They’re vicious to you online.'”

“I do not have the mental fortitude to go back to high school and experience it that way, with social media. I would just crumble!” Jayne laughed. “But it was really interesting speaking to [students] and trying to understand their experience now, and bring it to the movie [in a way that would] resonate with today’s audience.”

Mean Girls opens in theaters Jan. 12.