Last month, Geoff Glaab was waiting at a stop light in Louisville, Kentucky when he saw a driver two lanes over watching a Youtube video about tearing down a car engine. Glaab could hear the audio clearly because the driver had the volume very high. While the driver was at the light, Glaab could see him looking down at his phone.

Glaab primarily gets around by walking or biking and says he sees “far more than my fair share of distracted drivers.” But he told Motherboard he’s recently noticed an increase in people watching video and FaceTiming while driving.

“I don't know when people began to think this was a good idea,” Glaab said, “but here we are.”

Amazingly, it is perfectly legal for drivers in Kentucky to watch Youtube or any other video while driving. Kentucky only explicitly bans texting while driving and provides exemptions for using GPS functions and punching in phone numbers. It also doesn’t forbid browsing social media or other app-like functions. In a 2015 Courier Journal story about how hard it is to enforce the texting-while-driving ban, state trooper Paul Blanton said, “The way the law is written, you could be driving down the road playing Angry Birds.”

Kentucky may be an extreme case of weak distracted driving laws, but it is hardly alone. Many states have laws that were written at a time when panic regarding texting while driving was at its peak. Every state except Montana enacted some kind of texting while driving ban, and 27 states ban hand-held phone conversations. But at the time these laws were written, streaming video on phones was not nearly as common as it is now, nor were wireless network speeds fast enough to make it worth doing while driving. Therefore, many of the laws are vague at best about whether watching video while driving is illegal.

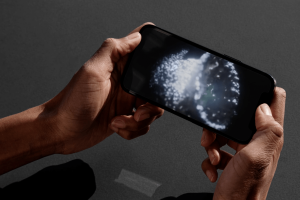

“Distracted driving” became a major safety subject in the mid 2000s with the proliferation of cell phones. There is no debate among experts that distracted driving is dangerous—comparable, according to some studies, with driving under the influence. In 2021, 3,522 people died in distracted driving crashes, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, a number that has remained relatively steady since 2010 despite countless public service advisories, ad campaigns, and other educational initiatives. But distracted driving rates are only increasing, because most drivers now have phones mounted in front of them at all times and also most new cars come with gigantic screens built into the dash compatible with streaming services and gaming devices.. And some people are taking it to new heights by watching full-on videos, live TV, Netflix, and other streaming content while driving.

In the past few months, I have personally seen four drivers watching videos as their cars passed me. It was easy to notice because the phones were mounted on the dash. One was watching football, another baseball, and the other two some random video I couldn’t discern. Two Motherboard staffers told me they’ve recently been in Ubers where their drivers were watching TV on iPads mounted next to the center console. (Uber spokesperson Gabi Condarco told Motherboard, “When signing up for the Uber platform, couriers and drivers agree to our Community Guidelines which clearly state drivers are expected to maintain an environment that makes riders feel safe, and reports of dangerous driving may result in account deactivation.”)

The rise in watching-while-driving is not merely a matter of anecdata. Last year, an Insurance Institute for Highway Safety survey on distracted driving found about 25 percent of drivers reported watching movies, TV shows, or video clips while driving at some point in the last 30 days, with about 15 percent saying they did so regularly. About 20 percent said they made video calls regularly in the previous month and about 15 percent recorded and posted video. Although “distracted driving” is most commonly associated with teens in public service campaigns, millennials aged 25-34 had the highest rates of watching videos, playing games, and scrolling social media while driving. Unsurprisingly given how central smartphones are to their work, gig economy workers like rideshare drivers reported they were four times as likely to engage in distracted driving behavior.

There are two types of laws that speak to watching videos while driving, according to IIHS assistant general counsel Danielle Wolf. The first is distracted driving laws specifically targeting cell phone use. Currently, eight states—Alabama, Alaska, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Massachusetts, Tennessee, and West Virginia—clearly ban watching video while driving under such electronic device laws. Four more “arguably” ban it, according to Wolf—Connecticut, DC, Washington, Wisconsin—because their laws define distracted driving as anything that diverts attention from the driving task.

Separately, 35 states have bans on screens in the driver’s line of sight, Wolf says. But several, such as New York, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and South Dakota, are specific to television and television broadcasts and therefore wouldn’t necessarily apply to internet videos or FaceTiming. Several other states like Oregon, Utah, and Texas have screen-in-view laws but the language may not apply to phones or tablets mounted on dashboards because they refer to vehicles “equipped” with certain characteristics or vehicles having screens “installed.”

Overall, Motherboard found 18 states definitely ban watching videos on phones while driving, 19 might depending on how the law is interpreted, and 14 almost certainly do not.

Still, having a law in place doesn’t necessarily mean people will stop doing something. Texting while driving is illegal in every state except Montana, but plenty of people still do it; almost 50 percent, according to the IIHS study. Still, such bans have been associated with reduced rates of vehicle crash emergency room visits and are generally credited with reducing texting while driving in general.

IIHS spokesperson Joseph Young told Motherboard he isn’t aware of any research that specifically ties watching videos to a certain level of crash risk, but added “it isn’t a big leap to assume that drivers watching videos or engaging in video calls will have their eyes off the road more of the time, which we know increases risk.”